Nordic Elegance – Material, Restraint & Structure

A Language of Refinement

Nordic elegance is often mentioned, but rarely described with clarity. It is not simply a style or a decorative approach. Instead, it is a way of balancing materials, proportion, and a quiet sense of luxury rooted in craftsmanship. It favors understatement over display and allows materials such as wood, brass, glass, pine, and ceramics to speak on their own terms. This approach is also fundamentally human; tactile, warm, and shaped for everyday domestic life rather than for monumental effect.

This sensibility emerged across Sweden and Denmark during the interwar and postwar decades, shaped by both local craft traditions and the broader modernist project. Designers worked not to overwrite material, but to reveal it, and objects were made to serve their function without excess. The pieces gathered here illustrate this approach across different scales and mediums – from seating and cabinetry to lighting, ceramics, and mirrored metalwork.

Order, Proportion & The Domestic Interior

Storage furniture in the mid-century Nordic home served as both architecture and display. The freestanding units designed by architects and cabinetmakers functioned physically as partitions, bookcases, and containers of domestic culture – books, glassware, ceramics, textiles – objects that reflected the intellectual and aesthetic life of the home.

This very rare freestanding bookcase and storage unit, designed by Arne Vodder in collaboration with Anton Borg and produced by Vamo Møbelfabrik in the 1950s, reflects this architectural quality. Constructed in teak with modular configurations of shelves, drawers, and sliding-door cabinets, its proportions form a cohesive elevation rather than a set of discrete components. Tapered legs lift the structure lightly from the floor, and the finished rear allows the unit to perform as a room divider. The impression is one of clarity, practical in use, yet refined in character.

Craft & Modernism in Lighting

Lighting brought another layer to Scandinavian modernism, mediating atmosphere through material and reflection. In the postwar period, Swedish glassworks developed a refined language of light, where crystal and brass were used to sculpt illumination rather than merely emit it.

This rare pair of floor lamps, designed by Carl Fagerlund and produced by Orrefors in the 1960s, exemplifies this approach. The slender brass stem is accented by five clear glass elements, creating a vertical articulation that feels architectural in profile. Velvet shades soften the light, while the circular glass bases provide stability while maintaining visual weight. Fagerlund’s work demonstrates the Nordic belief that elegance arises not from ornament, but from precision.

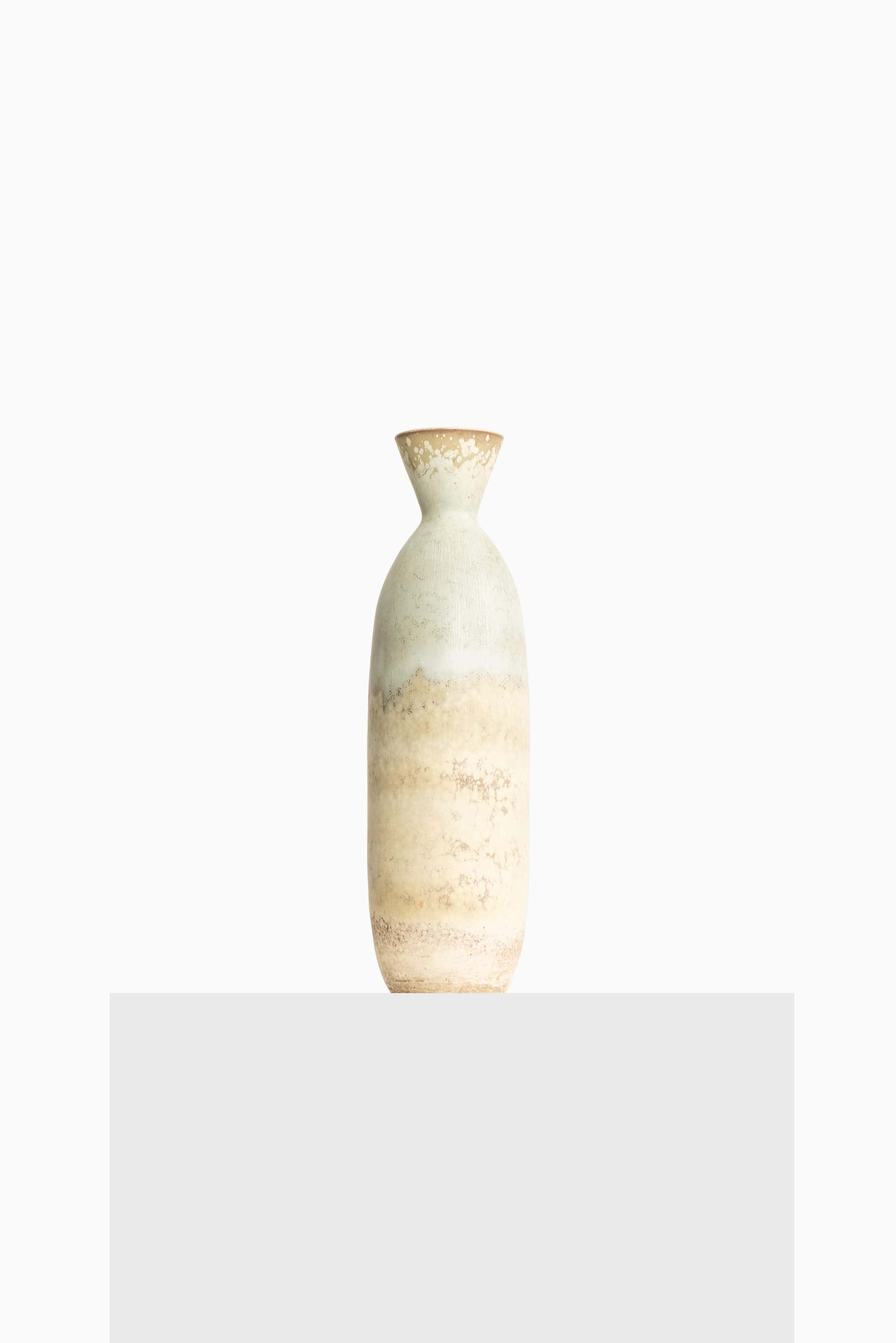

Surface, Texture & The Ceramic Imagination

Ceramics provided a parallel field for experimentation, where surface replaced structure as the primary medium. Swedish ceramists favored atmospheric glazes and geological tones, often working in dialogue with nature rather than abstraction.

The tall floor vase by Carl-Harry Stålhane, produced by Rörstrand in the 1950s, is a study in controlled texture and tonal variation. Its cylindrical body rises into a flared, concave rim, while layered glazes in pale green, cream, and beige evoke mineral sediment rather than figurative ornament. The matte finish and subtle speckling foreground the hand of the maker, reinforcing Stålhane’s instinct to let naturalism replace decoration.

Structural Gesture & The Discipline of Seating

Seating is where craftsmanship becomes anatomical. In Danish modernism especially, structure was refined to the point where the frame suggested motion, balance, and proportion independent of upholstery or pattern.

Hans J. Wegner’s Cowhorn armchairs, designed in 1952 and produced by Johannes Hansen, display this sculptural discipline. Carved from solid teak, the continuous rail that forms the chair’s back and arms reads as a single gesture, taut and muscular. Vegetable-tanned leather seats age into warm caramel tones, while finger joints and exposed transitions reveal technical mastery rather than conceal it.

If Wegner represents the precision of cabinetmaking, Axel Einar Hjorth represents the tectonics of timber. His Lovö armchairs, designed in 1932 for Nordiska Kompaniet as part of the Sportstugemöbler series, merge vernacular furniture with the spirit of modernism. Acid-stained pine, wrought iron fittings, and gently curving backrests produce a rustic clarity – rooted in landscape, leisure, and Swedish cultural identity.

Reflection, Geometry & The Modern Interior

Svenskt Tenn’s early modernism reveals yet another dimension of Nordic elegance: ornament expressed as geometry and craft rather than as flourish. Björn Trägårdh’s rare mirror from the 1930s frames its surface with braided pewter and brass, a union of cool and warm metals that is both decorative and precise. The interwoven pattern is close to architectural detailing, proving that restraint and ornament are not mutually exclusive.

Conclusion

What binds these works together is not uniformity, but discipline. Each piece speaks through limitation: a restricted palette of materials, a measured approach to proportion, a confidence in craft. Nordic elegance thrives not on abundance, but on choosing only what is necessary – and executing it with care.